Domestic cattle (Bos taurus) are possibly the most important species of domestic livestock bred by man. All breeds of domestic cattle descend either from the wild primeval cattle (Bos primigenius-primigenius) inhabiting Eurasia and North Africa or the Indian primeval cattle (Bos primigenious namadicus) inhabiting the Indian Subcontinent. The last representative of European wild cattle (Aurochs) died in central Poland in 1627. Other species of the Bovini domesticated later in Asia were, the Asian Waterbuffalo (Bubalus bubalis bubalis), the Yak (Bos grunniens), the Javan Cattle (Bos javanicus) and the Gayal (Bos frontalis). On the other hand several species of the same genus were never domesticated, such as the African Buffalo (Syncerus cafer) and the European and North American Bison (Bison bonasus and Bison bison).

European cattle were first domesticated 10,000 years ago in the Mesopotamia region and Indian cattle (Zebu) in the Hindu river valley approximately 2,000 years later. Archaeological findings from Crete, Macedonia and Thessaly indicate that cattle arrived in Greece 8,500 years ago with the first Near Eastern settlers.

Human migrations introduced domesticated cattle throughout the world. Besides producing milk and meat, cattle were the main ‘beasts of burden’ employed in the cultivation of land and as draft animals for transporting all kinds of loads. Moreover, cattle provided a series of valuable products such as skins, horns, hair, bones and manure. These were put to multiple uses, such as in heating, lubrication, upgrading of arable land, the manufacturing of clothes, tools, medicinal preparations, weapons, building materials etc.

Because of their size, cattle are among the most impressive of domesticated animals inspiring most ancient civilizations to worship bull and/or cow-like deities such as the Sumerian gods Anu and Ninhursag and the Egyptian sacred bull Apis, offspring of the goddess Hathor whose image was cow-like.

Greek mythology abounds in myths involving cattle. Notable examples are Io’s (Zeus’s mistress) transformation into a cow and her traversing the Bosporus straits (‘bos’ is ‘cattle’ in Greek and ‘poros’ is ‘passage’), the abduction of Europe by Zeus disguised as a bull, the birth of Minotaur (half man-half bull) by Pasiphae wife of Cretan King Minos. The bull was worshipped by the Minoans as a sacred animal. Rituals in ancient Crete involved acrobatic leaping over the bull’s back (taurokathapsia).

Ancient Greeks honoured their gods with bull sacrifices as is immortalized on the Parthenon frieze depicting the Panathinaic festival procession. The sacrifice of 100 bulls (hecatomb), constituted the ultimate gesture of worship. The tradition of slaughtering bulls on religious occasions was preserved in the Christian era and is still practiced at a local village festival in Agia Paraskevi, in Lesvos.

In folkloric tradition the ox is esteemed for its calm temperament and its strong work ethic. Oxen are obedient, strong and in possession of great endurance which enables them to plough through clay soil for many hours or pull carts with heavy loads over hard trodden rural roads. Oxen compared to horses are slower moving but superior for their safe and steady pacing, their low maintenance cost as well as the added value of their meat and dairy products.

Agricultural production in Greece is greatly indebted to the work performed by cattle until the beginning of mechanization in the 1950s-1960s. This is especially the case in many swampy areas where the cultivation of land and transport of produce would have been impossible without the employment of cattle and water buffalos.

The foundations for homogeneous cattle breeds were laid in the 18th century in west and central Europe when regional populations were selectively bred to create pure breeds. By the middle of the 20th century the improved selected breeds were exported worldwide and gained global dominance. They are kept in pure bred herds or crossed with the autochthonous cattle breeds of each country, which breeds evolved mainly via natural adaptation to local conditions and climate. By 2010 in Europe alone 130 old breeds of cattle became extinct, while the remaining 50 % are facing extinction. In Greece, most regional cattle populations were shaped by natural selection with a minimum of human interference in terms of selective breeding or the importation of foreign breeds. The abandonment of traditional agriculture, the introduction of mechanization and monoculture, rendered cattle no longer essential as working animals in farming communities. The last autochthonous cattle populations were abandoned in isolated mountain areas or islands for carcass production, while improved foreign breeds were imported for the production of meat and milk, based on economic considerations. Greek bibliography of the late 1960s mentions 9 autochthonous cattle breeds of which 5 (Tinos, Chios, Corfu, Andros, Messara-Crete) are deemed irreversibly extinct. For the past 5 years Amalthia has been collaborating with the Agricultural University of Athens and the LMU University of Munich on the genetic identification of Greek cattle breeds and populations.

Vrahicheratiki |

Katerini |

Sykia |

Kea |

Prespa |

Orinis Kritis |

Rodopi |

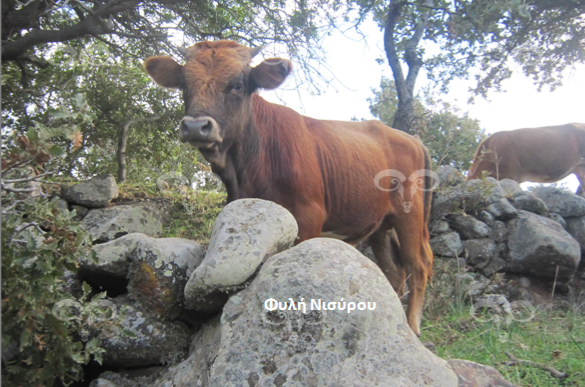

Nisyros |

Kastelorizo |

Agathonissi |

Greek Water Buffalo |